- Use lvm and thin pools with docker. It's far easier. You will simply need to mount the partition as /var/lib/docker at boot time (fstab entry). As far as underlying filesystem you have ext4,zfs,and btrfs. These all have pros and cons with ext4 being the current industry standard.

- Docker expects to run from a non-RAM based root filesystem since it uses pivotroot to jail the container. For that reason it's recommended that you setup an SD card with VFAT and Ext4 partitions. Once your SD card is partitioned, copy the boot images to the VFAT partition and extract the rootfs to the Ext4 partition.

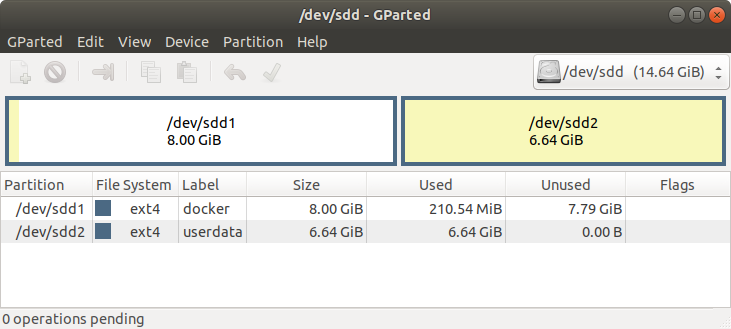

- Hence your host machine should have ext4 partition where docker is running and creating containers/ images from. $ sudo dockerd -storage-opt dm.basesize=50G. To let the changes take effect, you have to run the following commands: $ sudo service docker stop $ sudo rm -rf /var/lib/docker $ sudo service docker start.

Mar 24, 2016 Additional environment details (AWS, VirtualBox, physical, etc.): Physical Environment (8GB RAM, Core i5-4590, ext4) Steps to reproduce the issue: Install openSuSE 13.2. Run Iometer benchmark on the host. Run Iometer benchmark on a container based on SuSE. A data volume was used as the partition were to execute the benchmark. Use the BTRFS storage driver. Btrfs is a next generation copy-on-write filesystem that supports many advanced storage technologies that make it a good fit for Docker. Btrfs is included in the mainline Linux kernel. Docker’s btrfs storage driver leverages many Btrfs features for image and container management.

I’m running Docker on Ubuntu Xenial with the following command. For certain reason it’s 15 times slower than Virtual Box on the same machine with ext4. It’s about 5 times slower on XFS. I have tried different configuration but couldn’t figure out why its such slow. Is there anyway we can optimize MySQL performance in docker?

docker run -d --env=“MYSQL_ROOT_PASSWORD=drupal” --name=mysql -p 3306:3306 mysql

MySQL restore test in VirtualBox

weikai@drupal:~$ time mysql vbox < drupal3.sql

real 2m12.081s

user 0m4.868s

sys 0m1.208s

MySQL restore test in Docker

root@e3488a990fde:~# time mysql -u root -p dockerdb < drupal3.sql

Enter password:

real 11m47.783s

user 0m4.784s

sys 0m13.316s

Docker for Mac is a desktop app which allows building, testing andrunning Dockerized apps on the Mac. Linux container images run inside a VM using a custom hypervisor calledhyperkit – part of theMoby open-source project. The VM boots from an.iso and has asingle writable disk image stored on the Mac’s filesystem in the~/Library/Containers/com.docker.docker/Data/com.docker.driver.amd64-linuxdirectory. The filename is eitherDocker.qcow2 or Docker.raw, depending on the format.Over time this file can grow and become large. This post explains

- what’s in the

Docker.raw(orDocker.qcow2); - why it grows (often unexpectedly); and

- how to shrink it again.

If a container creates or writes to a file then the effect depends on the path, for example:

- If the path is on a

tmpfsfilesystem, the file is created in memory.. - If the path is on a volume mapped from the host or from a remote server (via e.g.

docker run -vordocker run --mount) then theopen/read/write/… calls are forwarded and the file is accessedremotely. - If the path is none of the above, then the operation is performed by the

overlayfilesystem, ontop of anext4filesystem on top of the partition/dev/sda1.The device/dev/sdais a (virtual)AHCI device, whose code is in thehyperkit ahci-hd driver.The hyperkit command-line has an entry-s 4,ahci-hd,/.../Docker.rawwhich configures hyperkit to emulate an AHCI disk device such that when the VM writes to sectorxon the device,the data will be written to byte offsetx * 512in the fileDocker.rawwhere512is thehard-coded sector size of the virtual disk device.

So the Docker.raw (or Docker.qcow2) contain image and container data, written by the Linuxext4 and overlay filesystems.

If Docker is used regularly, the size of the Docker.raw (or Docker.qcow2) can keep growing,even when files are deleted.

To demonstrate the effect, first check the current size of the file on the host:

Note the use of -s which displays the number of filesystem blocks actually used by the file. Thenumber of blocks used is not necessarily the same as the file “size”, as the file can besparse.

Next start a container in a separate terminal and create a 1GiB file in it:

Back on the host check the file size again:

Note the increase in size from 9964528 to 12061704, where the increase of 2097176512-byte sectorsis approximately 1GiB, as expected. If you switch back to the alpine container terminal and delete the file:

then check the file on the host:

The file has not got any smaller! Whatever has happened to the file inside the VM, the host doesn’t seem toknow about it.

Next if you re-create the “same” 1GiB file in the container again and then check the size again you will see:

It’s got even bigger! It seems that if you create and destroy files in a loop, the size of the Docker.raw(or Docker.qcow2) will increase up to the upper limit (currently set to 64 GiB), even if the filesysteminside the VM is relatively empty.

The explanation for this odd behaviour lies with how filesystems typically manage blocks. When a file isto be created or extended, the filesystem will find a free block and add it to the file. When a file isremoved, the blocks become “free” from the filesystem’s point of view, but no-one tells the disk device.Making matters worse, the newly-freed blocks might not be re-used straight away – it’s completelyup to the filesystem’s block allocation algorithm. For example, the algorithm might be designed tofavour allocating blocks contiguously for a file: recently-freed blocks are unlikely to be in theideal place for the file being extended.

Since the block allocator in practice tends to favour unused blocks, the result is that the Docker.raw(or Docker.qcow2) will constantly accumulate new blocks, many of which contain stale data.The file on the host gets larger and larger, even though the filesystem inside the VMstill reports plenty of free space.

SSD drives suffer from the same phenomenon. SSDs are only able to erase data in large blocks (where the“erase block” size is different from the exposed sector size) and the erase operation is quite slow. Thedrive firmware runs a garbage collector, keeping track of which blocks are free and where user datais stored. To modify a sector, the firmware will allocate a fresh block and, to avoid the device fillingup with almost-empty blocks containing only one sector, will consider moving some existing data into it.

If the filesystem writing to the SSD tends to favour writing to unused blocks, then creating and removingfiles will cause the SSD to fill up (from the point of view of the firmware) with stale data (from the pointof view of the filesystem). Eventually the performance of the SSD will fall as the firmware has to spendmore and more time compacting the stale data before it can free enough space for new data.

A TRIM command (or a DISCARD or UNMAP) allows afilesystem to signal to a disk that a range of sectors contain stale data and they can be forgotten.This allows:

- an SSD drive to erase and reuse the space, rather than spend time shuffling it around; and

- Docker for Mac to deallocate the blocks in the host filesystem, shrinking the file.

Docker Slow Ext4 Partition File

So how do we make this work?

In Docker for Mac 17.11 there is a containerd “task”called trim-after-delete listening for Docker image deletion events. It can be seen via thectr command:

When an image deletion event is received, the process waits for a few seconds (in case other images are beingdeleted, for example as part of adocker system prune) and then runs fstrim on the filesystem.

Returning to the example in the previous section, if you delete the 1 GiB file inside the alpine container

then run fstrim manually from a terminal in the host:

then check the file size:

The file is back to (approximately) it’s original size – the space has finally been freed!

There are two separate implementations of TRIM in Docker for Mac: one for Docker.qcow2 and one for Docker.raw.On High Sierra running on an SSD, the default filesystem isAPFSand we use Docker.raw by default. This is because APFS supportsan API for deallocating blocks from inside a file, while HFS+ does not. On older versions of macOS andon non-SSD hardware we default to Docker.qcow2 which implements block deallocation in userspace which is more complicated and generally slower.Note that Apple hope to add support to APFS for fusion and traditional spinning disks insome future update– once this happens we will switch to Docker.raw on those systems as well.

Support for adding TRIM to hyperkit for Docker.raw was added inPR 158.When the Docker.raw file is opened it callsfcntl(F_PUNCHHOLE)on a zero-length region at the start of the file to probe whether the filesystem supports block deallocation.On HFS+ this will fail and we will disable TRIM, but on APFS (and possibly future filesystems) thissucceeds and so we enable TRIM.To let Linux running in the VM know that we support TRIM we set some bitsin the AHCI hardware identification message, specifically:

ATA_SUPPORT_RZAT: we guarantee to Read-Zero-After-TRIM (RZAT)ATA_SUPPORT_DRAT: we guarantee Deterministic-Read-After-TRIM (DRAT) (i.e. the result of reading after TRIM won’t change)ATA_SUPPORT_DSM_TRIM: we support theTRIMcommand

Docker Slow Ext4 Partition Software

Once enabled the Linux kernel will send us TRIM commands which we implement withfcntl(F_PUNCHOLE)with the caveat that the sector size in the VM is currently 512, while the sector size on the host canbe different (it’s probably 4096) which means we have to be careful with alignment.

The support for TRIM in Docker.qcow2 is via theMirageqcow2 library.This library contains its ownblock garbage collectorwhich manages a free list of TRIM’ed blocks within thefile and then performs background compaction and erasure (similar to the firmware on an SSD).The GC must run concurrently and with lower priority than reads and writes from the VM, otherwiseLinux will timeout and attempt to reset the AHCI controller (which unfortunately isn’t implemented fully).

Theqcow2 formatincludes both data blocks and metadata blocks, where the metadata blocks contain references to other blocks.When performing a compaction of the file, care must be taken to flush copies of blocks to stable storagebefore updating references to them, otherwise the writes could be permuted leading to the reference updatebeing persisted but not the data copy – corrupting the file.Sinceflushes are very slow (taking maybe 10ms), block copies are done in large batches to spread the cost.If the VM writes to one of the blocks being copied, then that block copy must be cancelled and retried later.All of this means that the code is much more complicated and much slower than the Docker.raw version;presumably the implementation of fcntl(F_PUNCHHOLE) in the macOS kerneloperates only on the filesystem metadata and doesn’t involve any data copying!

As of 2017-11-28 the latest Docker for Mac edge version is 17.11.0-ce-mac40 (20561) – automatic TRIMon image delete isenabled by default on both Docker.raw and Docker.qcow2 files (although the Docker.raw implementationis faster).

If you feel Docker for Mac is taking up too much space, first check how many images andcontainers you have with

docker image ls -adocker ps -a

Docker Slow Ext4 Partition Download

and consider deleting some of those images or containers, perhaps by running adocker system prune):

The automatic TRIM on delete should kick in shortly after the images are deleted and free the spaceon the host. Take care to measure the space usage with ls -s to see the actual number ofblocks allocated by the files.

If you want to trigger a TRIM manually in other cases, then run

To try all this for yourself, get the latest edge version of Docker for Mac from theDocker Store.Let me know how you get on in the docker-for-mac channel of theDocker community slack.If you hit a bug, file an issue ondocker/for-mac on GitHub.